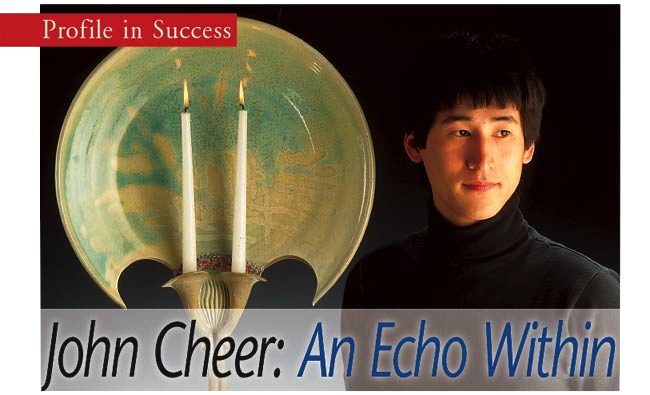

porcelain and crushed glass, measuring 20 inches by 33 inches by 4 inches, by John Cheer.

Cheer was born in China in 1966, at the time of its Cultural Revolution, a period characterized by social and economic chaos. When he was 12 years old, his family immigrated to the United States and settled in Torrance, a suburb of Los Angeles, Calif. Sadly, Cheer’s father died when he was in high school, and his mother, who had no job at the time, went to live with Cheer’s sister, who was attending the University of California-Los Angeles on a scholarship. Left on his own, Cheer lived in a friend’s garage while he attended West High School in Torrance. To support himself, he worked after school at a number of jobs, preferring to wait tables or wash dishes at a restaurant for the free meals.

While in high school, Cheer, who says he had always been drawn to the visual arts, took a ceramics class with the first of two teachers who would turn out to be significant influences on his work. One day, the teacher, who always supported and encouraged students’ ideas, was demonstrating how to throw a pot on the wheel. “I thought it looked easy,” Cheer says. “He made it look easy. ‘I can do that!’ I told him. So he gave me a piece of clay. I ended up wearing it!”

Nevertheless, Cheer persisted until he controlled the clay rather than allowing the clay to control him, he says. Then, he discovered that he could begin any form on the wheel much faster than hand-building it, before sculpting and refining it.

“Well, I had this Plymouth Duster …”

At the same time Cheer was honing his skills in clay he was also developing another skill — bodywork of the vehicular kind.

He had bought a souped-up Plymouth Duster for $800. It had velvet seats, a chrome steering wheel, big back tires, and a rear end that elevated when Cheer pushed a button on the dashboard. What he didn’t know was that he had purchased a car designed for a gang member. “Because of the cultural differences, I didn’t understand this at the time,” laughs Cheer.

The car looked spectacular, says Cheer, but it had constant mechanical problems. To save on repair costs, Cheer enrolled in a mechanics course at a vocational technical school to learn basic repairs. Despite his best efforts, however, the car finally broke down and Cheer was unable to fix it. While it was being towed to a garage, someone crashed into the tow truck and into the Plymouth Duster. … The estimated repair bill was $2,500 — three times more than he had originally paid for the car and more than someone living in a friend’s garage could afford!

To Cheer, the solution was obvious. He signed up for another course, this time in auto body work, paying for it with the $200 he won in small claims court from the driver in the accident. While learning to repair the car, he also learned how to work with metal, how to do torch work, and how to put a car frame back into shape. When he was finished the course, not only did he have a working car again, but he had gotten a job as a freelance body shop worker.

With the money he made from “body-shop hopping,” Cheer says, when he graduated from high school, he was able to enroll in El Camino College in Torrance to study ceramics. He was now supporting himself and his mother, who moved in with him once he had an apartment of his own.

After finishing the two-year program, he continued doing body work and eventually started his own business on a small scale. He rented time from someone else’s shop, using the space and equipment on weekends, when the shop was normally closed.

From the Far East to the East Coast

Just as Cheer was seriously considering investing in his own body shop and equipment, two things happened. First, California passed a law that toughened the penalties for drunk driving, Cheer says, which significantly reduced the demand on bodywork and had a severe effect on business. Second, Cheer’s sister finally convinced him to move to Pennsylvania, where she had relocated with her husband.

So, in December of 1991, Cheer and his mother moved to Allentown, Pa. “It was a shock! My sister and my mother (who had visited my sister there many times) kept telling me about the trees — all the beautiful trees. But, in December, there are just a lot of bare branches!” But, after two years of uncertainty about the move east, Cheer says he finally began to appreciate the change of seasons.

While living with his sister, he took some body shop jobs on the side and registered for a ceramics class at Moravian College, taught by Renzo Faggioli, Master Craftsman Ceramics from Florence, Italy. Faggioli soon became Cheer’s second valued teacher. “He was very good. He taught me how to mix glazes and work in contemporary forms. We became good friends,” Cheer explains.

Cheer also became Faggioli’s studio assistant, and was able to produce his own work and experiment with different techniques. In 1993, he began selling his work at one or two local shows a year, and his intentions of opening a body shop quickly fell to the wayside. “I thought then that if I didn’t [make it with] a full-time business doing ceramics, I would go back to body work,” he says.

Ceramics or body work, though, Cheer knew he had to work for himself. He bought a house and spent most of his remaining money on equipment. While looking for an electric kiln, a local gallery owner told him about a community college that was building a new ceramics studio and was taking closed bids on the old equipment, including a huge, 5-ton gas kiln. Believing it to be way beyond his budget, Cheer still put in a bid that he could afford -— $500. “A few weeks later, I get a call. I had won! … Then I thought, ‘Where am I going to put it?’”

He dug a large area, six inches deep, in his backyard and poured a concrete slab to support the weight of the kiln. Then he spent $1,000 to move it to his yard.

For three years, Cheer worked contentedly in his basement studio and fired in his backyard kiln — until a new neighbor moved in across the street … and didn’t like the looks of the kiln. “She started a petition in the neighborhood stating the kiln would depreciate her property,” says Cheer. “I am two blocks from the Projects!”

Trying to make the neighbors happy, the zoning board told Cheer he could keep the kiln if he had 30 feet of property clearance all the way around it. “That would have put it in my living room!” he laughs.

Adapting to Diversity

He surrendered to the inevitable and moved his studio and kiln to a location near the river in a run-down area with an adult video store on one side and a mechanic’s garage on the other. Though his ceramist friends thought he would never last a year in such a neighborhood, Cheer established friendly relations with his new neighbors and has had no problems in seven years — and no petitions.

After a few years of doing local shows and selling lots of mugs, Cheer decided to focus on more creative work. “My god, I used to sell so many mugs, I thought I might as well get a job as keep this up,” he recalls.

So he continued to experiment with different techniques and materials. With scuba diving among his favorite hobbies, Cheer finds inspiration for the colors and forms of his work in water and sea life. In an attempt to capture the transparent and light-reflective nature of water, he began looking for ways to incorporate glass into his work.

It took four and a half years of trial and error, and the burying of many failures in the backyard, before he discovered a technique for incorporating the glass at a level of quality that satisfied him. The technique involves the formulation of a glaze that acts as a binding agent between the clay and the glass. He fires Cone 12, a heavy-duty reduction, using propane rather than natural gas. The firings take 12 hours, and the kiln takes another day and a half to two days to cool. The result is a combination of glass and clay that gets its texture from the cracking patterns of the glass, depths of color, and shine — the look for his stingray forms that he desired.

Looking for venues for this new body of work, Cheer talked with other artists, and read magazines like The Crafts Report for show information. He applied to and exhibited at shows up and down the East Coast.

“I used to have a small truck that I loaded with all my pieces. I packed them in the bed of the truck and even in the passenger seat so tightly I couldn’t move,” Cheer laughs. “If I pulled over to the side of the road to rest, I had to rest in the same position as when I was driving!”

Cheer finds such aspects of being a one-person business the most challenging. “I have to wear so many hats — shopkeeper, driver, delivery boy, cleaner, bookkeeper, artist and business man.” Add to that father to his five-year-old daughter, Sasha, who he cares for one or two days a week while his wife, Diane, works as a respiratory therapist.

“I know I have to produce so much a year to support myself and my family, which means so many pieces a day, and so many minutes per piece. I say, ‘Okay, I can spend 30 minutes on this piece.’ But as I am working on the piece, something happens; I look at the clock and three hours have gone by. I can’t always control time.”

For Cheer, whose work ranges in price from $35-$6,000, it is a constant effort to balance production demands with his artistic needs. It is the main reason he chooses to do only retail — he does not have enough inventory and he can’t increase production without losing his creativity, he says. “I want my work to not only be unusual, but evolutionary, as well as a discovery process.”

Another challenging aspect of the business for him is jurying into shows and balancing his schedule, knowing that for most shows there is no guarantee. He can send great slides and not get in, and lesser quality slides and get in, he says. “I realized I am a full-time gambler now!”

But in spite of all the challenges of culture, economics and neighbors, Cheer does manage to make a living. And thanks to his adventurous spirit, he wants to see how far the work will take him — perhaps into blown glass and metals, to incorporate his experience in body work. “For me, there is a gratification [in creating] an echo of something greater than us within ourselves.”

| John Cheer 141 East Cumberland St. Allentown, PA 18103 (610) 782-9880 |

| cheerclaystudio@yahoo.com |

Paula Chaffee Scardamalia is a Berne, N.Y.-based freelance writer who teaches and owns her own weaving business, Nettles and Green Threads. She is also a creativity coach for artists and writers. REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION from The Crafts Report March 2002 online issue.

| Crafts Report Website: https://www.craftsreport.com/ Subscription Questions: Subscription Services Dept. Letters to the Editor Technical Problems: Web Editor |

The Crafts Report P.O. Box 1992, Wilmington, DE 19899 (800) 777-7098, (302) 656-2209 fax (302) 656-4894 |

| Biography of John Cheer John Cheer was born in 1966 in Communist China and raised in Shanghai and Peking. As a child, he had a natural gift for taking things apart and putting them back together again. At the age of 8, he spontaneously made an entire Chinese circus out of child’s clay, in miniature, including every act from bicyclists to twirling plates. After living in Hong Kong for two years, he immigrated with his family to California at age 13 and became a U.S. citizen. John speaks Mandarin, Shanghainese, Cantonese and English. During his high school years, an inspirational art teacher led him to pursue his interests in clay and sculpture. While rising to the challenge of supporting himself in high school, he also studied auto body and mechanics and eventually had his own small auto body and paint business. In 1991, he relocated to the northeast and in 1993 became a full-time clay artist, selling his work at fine art and craft shows throughout the country. His early work was traditional and functional, gradually evolving over the years into decorative and abstract contemporary. The majority of finished pieces combine fused clay and glass. In recent years, he has added copper wire into some creations. John does about 24 shows per year, primarily along the east coast and the south, but has gone as far as Texas, Colorado, and Arizona. He has won over 55 awards for his work over the years at fine art and craft shows. He has been featured in Ceramics Monthly and Crafts Report and exhibited his “Soul Search” lamp and fountain at the State Museum in Harrisburg, PA. John has a knack for creatively transforming life’s adversities, plus a mechanical aptitude to fix anything that is broken. He presently lives in northeastern PA with his family. |

| Awards John has won over 55 awards in the last 15 years including many “Best of Show” and “1st Place in Ceramics” at fine art and craft shows. ArticlesMarch 2004 – Ceramics Monthly Magazine March 2002 – Crafts Report Magazine Feature article – “John Cheer: An Echo Within” May 1999 – Sunday Patriot-News, Harrisburg, PA Feature article – “East Meets West in Art” May 1995 – Ceramics Monthly Magazine Group ExhibitionsMay 2007 – Greenshire Arts Consortium Quakertown, PA June 14 – Sept.14, 2003 – State Museum Harrisburg, PA “Art of the State: PA 2003” March 1994 – Paramount East Peekskill, New York. “Trends in American Design” InstallationsNovember 2006 “Chandelier of Ice and Light” Winterfaire 2006 Upper Black Eddy, PA (tree branches, plastic water jugs, paper, water, miniature lights) July 2005 “Giant Kapok Tree” International Summer Arts Camp Musical Theatre Upper Black Eddy, PA (fiberglass, paint, live tree branches with leaves)Related Activities2005 – Taught a specialty camp for children ages 5-12. Wheel-throwing and making hand-built clay ocarinas. River Valley Waldorf School. Upper Black Eddy, PA 1992 – John was a substitute ceramics teacher at Baum School of Art in Allentown, PA 2002 – Moravian College in Bethlehem, PA. He has done workshops for elementary schools and taught private ceramics classes in his home studio. Galleries Featuring John Cheer CeramicsChora Leone Gallery – Somers Point, NJ Ava’s Glass Gallery – Quakertown, PA Cleo’s Silversmith Shop and Gallery – Bethlehem, PA Topeo Gallery – New Hope, PA Stonehedge Gardens and Originals Gift Shop – Tamaqua, PA |